What follows is adapted from the content of a presentation I gave at the November 2024 Critical Voices Network Ireland conference. The theme of the conference was on responding to iatrogenic harm in mental health.

———————————————————————————–

Some time ago, I attended a launch event for a coalition of organisations working locally for people with issues around homelessness, addiction, offending and mental health. Just before the start, I introduced myself to two middle-aged women, who happened to work at a hostel nearby. The main thing I recall about the conversation is their remarking, about the issue of mental health in their line of work:

“Once you’ve got that, you don’t get better.”

I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t. But, in a way, they were making a valid point, because, all too often, that seems to be the trajectory for mental health service users. They don’t get better.

Receiving psychiatric treatment is often associated with disability, and sometimes even a deteriorating outlook. Understanding the dynamics leading mental health professionals to inadvertently contribute to iatrogenic harm is, I contend, essential for addressing these trends.

I try here to scratch the surface of some of those dynamics. In my view, they stem principally from:

- the assumptions, often tacit, made about someone presenting with mental health symptoms, and the danger of those assumptions.

- a lack of recognition, in practice, of the full range of effects and consequences of psychiatric prescribing.

As the theme is inadvertent harm, I’m not discussing issues like restraint, coercion or abuse. Also, I won’t dwell here on more obvious examples of poor practice or negligence – perhaps arising from a lack of diligence in reviewing medical records, or in following guidance. Where, for instance, drugs shown already to be ‘non-therapeutic’ for the patient are re-prescribed, or a contra-indicated drug is prescribed.

My focus here is on harm that may occur when treatment is within, more or less, the ‘standard of care’ according to the relevant professional bodies.

While I don’t think this this aspect of iatrogenic harm can be properly addressed, without wider changes in the regulation of the pharma sector; establishing checks against the commercialisation of healthcare research. I won’t try to add to what others, better placed than me, have documented before about certain practices of the pharmaceutical industry.

That’s an issue on the supply-side as it were. What about the demand for mental health services?

Well, that demand arises from society, and will obviously tend to reflect social problems. Over the last decade or so, the tongue-in-cheek, spoof diagnosis of ‘shit-life syndrome’ has entered public debate. With a recognition from overwhelmed GPs and other practitioners that they can’t properly address issues — arising from deprivation or harrowing personal circumstances — just by doling out a prescription for an antidepressant. And that doing so often isn’t inappropriate. The idea carrying with it the implication that society has been “overmedicalising” the problems of living that its members can face.

Many factors have driven that ‘overmedicalisation’. But one that some critical commentaries have pointed to is the use of symptom-based rating scales for issues like; depression, anxiety or ADHD. These tools can mark people that are reasonably healthy, but may be struggling with challenges in their lives, as being over a threshold for some diagnosable mental health condition. Thus resulting in more prescriptions of antidepressants, anxiolytics, or stimulants, than is really warranted.

According to this view:

“Symptom — based logics generate inflated prevalence estimates…”

My intuition is that this inflated prevalence is due, both to the origins of such ‘symptoms’ and to the nature of commonly held assumptions about diagnoses. Essentially, that:

- ‘symptoms’ have multiple potential causes.

- whereas, a diagnosis usually attributes them to a single condition.

Putting these two features together, one can see, I hope, how an inflation of a diagnosis’ commonplaceness may occur.

These critical commentaries have generally pointed to the role of vested interests in creating and maintaining the use of these tools. Indeed, the GAD7 and PHQ-9 questionnaires were formulated by psychiatric experts contracting for Pfizer.

Filling-in such questionnaires while visiting a GP, or other treatment centre, you might with a ten or fifteen minute consultation be prescribed an SSRI (the go-to choice among the drugs used as ‘antidepressants’.) In the nineties they told us they had the answer to life’s unhappinesses, in the form of Prozac and its analogues.

Taking an SSRI may well activate you, give you some ‘get up and go’, or block out any worries you might have been having. But, this comes with some concerning, even alarming, possible effects. Links are seen with; impulsivity, aggression, suicidality, disinhibition, volatility, emotional blunting or indifference to others, loss of sensitivity…

As has become increasingly apparent since the nineties, once prescribed these drugs you are at greater risk of developing manic and/or psychotic symptoms. Other prescription drugs can trigger mania or psychosis, include Ritalin or Adderall used for ADHD. These are amphetamines with dopaminergic effects. Individuals are five times more likely to develop psychosis after taking Adderall, according to this recent study.

‘Unmasking’

If you do go on to suffer such an episode, medics may subsequently tell you the SSRI has “unmasked” your ‘latent bipolar disorder’ (or latent … disorder). Implying, it would seem, that you’ve really always had latent bipolar. And that you weren’t diagnosed correctly before. But after this ‘unmasking’, you’ve now, thankfully, got your true diagnosis!

But, could they not more simply have said: “You appear to be more sensitive than average to the SSRI’s (etc) activating effects.”

In any case, you’d have gone from presenting with a milder type of complaint, to receiving a more serious diagnosis, and so to a more intense level of evaluation from services. Probably, you will now be prescribed an additional drug class, like a ‘mood stabilizer’.

Hybrid diagnoses and poly-pharmacy

In a case where someone on a SSRI for depression develops such an episode, and they’re assessed, say, as having ‘manic symptoms with some element of psychotic disturbance’. This would, quite likely, result in their receiving a diagnosis of ‘schizoaffective disorder’ – a diagnosis implying a grey area between ‘schizophrenia and ‘bipolar disorder.’

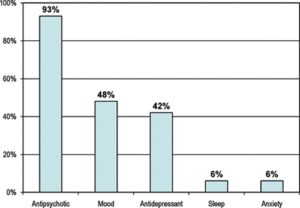

Be that as it may, the practical upshot of getting a schizoaffective diagnosis will probably be the prescription of two or three different drugs for ongoing treatment: ‘mood-stabilizers’ and ‘antipsychotics’, and perhaps an SSRI or SNRI.

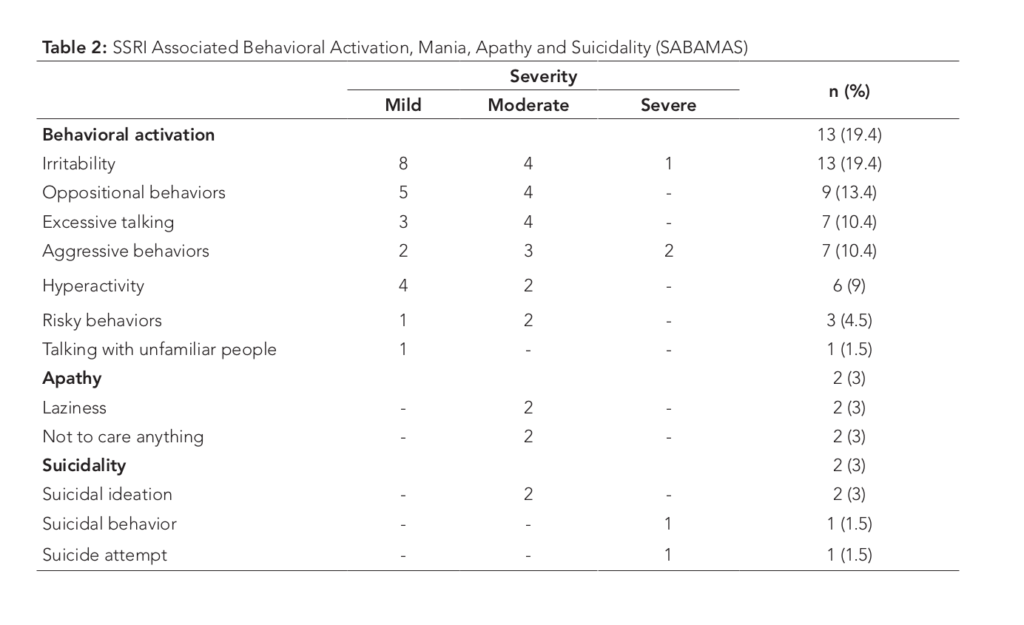

US data for 2008 – Nearly 40% with the diagnosis are prescribed three classes of drugs

‘Antipsychotic’ is, as J. Moncrieff has noted, really a marketing term for drugs otherwise known as ‘neuroleptics’ or ‘major tranquilizers’. Similarly ‘mood stabilizer’ is a term also used for ‘anti-epileptic’ or ‘anti-convulsant’ drugs. Both drug classes generally act as central nervous system suppressants, and come with their own set of adverse effects and probable morbidities.

So, that would, quite potentially, mean three sets of adverse drug-effects for those on such a maintenance treatment programme.

Taking the effects of just one of those drug classes, neuroleptics

Over time, you might find, as I did after a first hospitalisation, that you sleep and eat more than usual; have little interest in getting out and about; feel blank, not having much to say; with ‘impoverished’ – flat or slurred – speech.

Effects such as these will be taken, by many including quite possibly friends and family members, not as the effects of major tranquillizers, but as confirmation of your illness. Indeed, from a clinical perspective the outward effects of neuroleptic treatment are quite likely to be viewed as the ‘negative symptoms’ of a schizophreniform disorder.

Dr Peter Breggin made the case that the result of ongoing intake of such compounds will be what he has termed chronic brain impairment.

Among other risks, they can have potentially fatal effects on the heart. Even though the use of these drugs in general populations has been warned against, they’ve sometimes been used in the management of a prison populations, due to their tranquilising effects. One antipsychotic, ‘seroquel’ can even become a ‘drug of choice’. With some people seeking it, as a way to sleep-through in a stressful environment.

My own experience, of taking it as maintenance treatment, was that I could easily sleep up to 12 hours, and would still feel groggy after getting up.

Life as an outpatient

Thinking, at an everyday level, about the challenges service users face, I think we can start to see that society is putting conflicting demands on ‘service users’. It’s natural that families will expect a young person to ‘make something of their self’. And the government in Britain now expects mental health services to meet targets around employability; referring their patients onto work coaching programmes, volunteering, and so on.

But, how can service users be expected to make appointments, let alone search for a job and manage their household, if they are sleeping 12 hours a day?

It seems out-patients effectively face a dilemma:

- Comply with maintenance treatment: Accepting the limitations and potential longer-term health risks (Some who do this, I must admit, have relative stability in their lives and go on to enjoy the benefits of full-time employment. Although, my impression is this group tend to have strong support networks around them.)

- Or risk non-compliance: Which comes with potential complications that aren’t easy to manage.

The cumulative effect of extended treatment with neuroleptics will be for the brain to develop some propensity to dopaminergic hypersensitivity (or ‘supersensitivity’). Due to the brain’s compensatory adaptation to dopamine receptor blockade; more receptors grow. This results in their increased density in parts of the brain.

Thus, should you find the ‘side-effects’ of the drugs unpleasant or obstructive to your life, and not knowing all that about acquired ‘dopaminergic supersensitivity’ (I mean, why would you?) decide to take yourself off. You’re likely then to undergo the consequences of an effective surge in a dopaminergic signalling, and experience what’s called ‘rebound psychosis’ amidst other, more somatic withdrawal symptoms.

In treatment centres these type of events, typically, haven’t been understood as drug-withdrawal effects. More likely, they’re assessed as a ‘relapse’ of the condition for which you were prescribed antipsychotics. Or perhaps, those effects will be attributed to some new condition, that you are now said to have in addition to your pre-existing diagnosis.

But, even if you don’t discontinue your meds, that compensatory proliferation of dopamine receptors produces a potential sensitization – still there under the surface — which has likely heightened your susceptibility to stress and/or other fluctuations of the nervous system; including, for example, the effects of certain drugs (illicit or otherwise) that act on the dopaminergic or serotoninergic systems. Any ‘dabbling’ will then be more likely to result in a persistent episode. These events are, again, likely to treated by services as a ‘relapses’ or the appearance of some other diagnosable feature of a severe mental illness.

But, let’s say you are well behaved – staying on your neuroleptics and avoiding consumption of other drugs. Seeing you affected by features like; a lack of motivation, memory loss, impaired speech, facial masking, etc, your clinical team agree to try switching you to a different ‘antipsychotic’. The procedure of tapering the old drug and introducing the new one would likely be overseen in a relatively short time-frame, perhaps two weeks at most.

Among the options, the go-to choice for younger men with ‘schizophreniform’ diagnoses has been aripiprazole (Abilify). Marketed as having a low side-effect profile, by 2013–2014 it had the leading market share in the US.

Abilify was promoted as down-regulating brain systems associated with positive symptoms, while up-regulating circuits associated with negative symptoms. Things didn’t turn out so neatly.

Unlike most antipsychotics which are dopamine receptor antagonists, it is said to be a ‘partial dopamine agonist’ – sometimes described as ‘regulating’ dopamine rather than blocking it. It has some ‘affinity’ with the receptors, activating them to some degree.

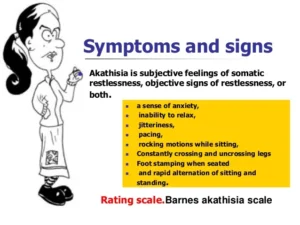

In switching someone who’s acquired dopaminergic supersensitivity to a partial agonist fairly abruptly, problems are likely, including; akathisia (intense restlessness), compulsions, and agitation. I would hypothesize that a large proportion of the people prescribed Abilify would have been pre-sensitized by taking standard D2 receptor blockading drugs beforehand. This, quite potentially exacerbating the drug’s adverse effect profile.

If you were unstable or in a crisis in life, akathisia symptoms, sleeplessness and tremors are unlikely to help and could even result in suicidality.

For staff in mental health services, it would though be quite easy for practitioners to mistake akathisia symptoms as being due to, say, an anxiety disorder, or perhaps stress from paranoid delusions. Especially, if those staff weren’t aware of the potential adverse effects of starting the drug.

Signs and symptoms of ‘generalised anxiety disorder and ‘akathisia’

There is some degree of overlap in the symptoms rated by this rating scale for akathisia and for example those found in the GAD7 anxiety scale, inferring a potential way that adverse drug (or withdrawal) effects could be misinterpreted. Similar overlaps between prescription drug effects and the symptoms associated with other diagnoses can be found.

Self-medication — kicking the can down the road.

Unpleasant prescription drug effects and sequelae can drive ‘self-medication’. Even at the milder end of akathisia — perhaps resulting from changes brought about by past exposure to psychiatric drugs – patients may seek relief through alcohol consumption, or benzos, etc.

As David Healy remarked in a recent of his presentations, alcohol can be an effective relief for akathisia symptoms. He was pointing to the role of SSRIs in driving some people to develop alcoholism. The calming effect of drinking, no doubt explains why many with complex issues will turn to it, to relieve feelings of unease or being on edge. Of course, this only a temporary answer.

Turning to substance use to suppress discomfort is likely to mean people stagnating in their current pattern of living. With the potential for some relapse or crisis event probably looming ever larger.

Psychiatric conditions or iatrogenesis?

One under-recognised aspect of pharmacological interventions is that they have some propensity to cause issues like ‘kindling’ and ‘sensitization’. Through which, even seemingly minor changes in levels of psychotropic or psychoactive compounds, hormonal fluctuations, or changes in the patient’s environment can precipitate crises.

One can argue, as I take David Healy as intimating, that these seemingly abrupt changes in clinical presentation – where people relapse ‘out of the blue’, or present with symptoms they haven’t previously – may well be manifestations of a (poly) ‘drug-evoked nervous system dysregulation’. In which, further drug interventions exacerbate the enduring consequences of past ones. And not the sudden re-emergence of a mysterious psychiatric illness, or people suddenly acquiring discrete new illnesses.

At the least, my contention is that such complications will often form an underlying thread through more chronic and seemingly intractable case histories.

******************

Part two will attempt to outline some of the wider contextual factors perpetuating these trends, and explore some more flexible approaches to causation and diagnoses.