This blog is a follow on part 2 from Neil’s earlier Part 1 featured Blog on Mad In Ireland

In part one, I tried to show how prescribing interventions might complicate people’s clinical presentations:

- ‘from initially presenting with some mild mental health issue, receiving a diagnosis and a prescription to potentially experiencing adverse effects from the prescribed drugs

- effects which are then often mistaken for symptoms of some ‘underlying condition’

- then receiving a more serious diagnosis and being prescribed other psychiatric drugs

- which could result in cognitive impairments or akathisia potentially leading to; additional diagnoses and a poorer prognosis; or the patient attempting to come off their psychiatric meds; or their feeling a need to ‘self-medicate’

- hence to complications from substance use and/or other psychiatric drugs, or their withdrawal effects,

- sometimes resulting in what are perceived as ‘relapses’ and the patient becoming a “frequent flyer” for services

When patients have spoken about withdrawal effects to doctors, all too often they haven’t been believed. There are a range of reasons for this; drug information provided by pharma may gloss-over adverse effects – including withdrawal syndromes; prescribers probably won’t be comfortable admitting to themselves, let alone anybody else, that their treatment decisions may’ve been harmful; until very recently, there has been a lack of adequate guidance on prescribed drug withdrawal from professional bodies; and many doctors will be too busy in daily practice to keep up to date with latest research and so on.

Further, the power imbalance between an authoritative psychiatrist and a troubled psychiatric patient makes it easy for the latter’s complaints to be dismissed as manifestations of mental illness. Those experiencing adverse effects or sequealae from treatment will often be assessed through a prism of psychiatric characterisations – potentially a weaponised vocabulary. It can be easy for professionals to discount their reports. Those with a psychiatric history (of being ‘well-known to services’) may find their perspective is disparaged. This can be considered a form of ‘diagnostic overshadowing’. Something I’ll return to later.

Breaking down some common assumptions about psychiatric diagnoses.

The natural implication of commonly used language, when people say, “she’s got schizo..” or “he’s got …”, effectively misapprehends the character of psychiatric diagnostics; passing over them as theoretical constructs, to assume they refer to some inherent feature of the patient’s biological makeup. The tendency is to reify a diagnostic construction into a real concrete property, that people with the diagnosis all supposedly have inside them. Typically, if a patient has more than one psychiatric diagnosis, they are taken as having discrete (separate) illnesses. Some patients and families do identify with these diagnoses, feeling that they have as many separate illnesses.

Such notions stem, in large part, from a psychiatric paradigm that had taken hold of the profession by the nineties, and are still, I’d say, reflected in practice and public attitudes. As Nancy Andreason outlined the ‘biomedical model’ in her 1984 book:

“The major psychiatric illnesses are diseases. They should be considered medical illnesses, just like diabetes…”

But the ‘broken brain’ paradigm was belied by the way diagnoses were incorporated into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. The late Paula Caplan, who was initially on the DSM IV committee, later related in her book that whether a diagnosis was incorporated into the DSM really depended on the subjective biases of committee members, personal anecdotes and office politics, and not any robust scientific criteria.

Schematising, in abstract terms, the formulation of a diagnosis, it might look like this:

- Identifying some cluster of symptoms that seem to present together

- Producing some checklist of symptoms, with perhaps some heuristics for differentiation from similar sets of symptoms

- This construct is given a name — ‘X’

- Proceeding, implicitly, to the claim that: Patients exhibit these symptoms because they ‘have X’.

This last is clearly vacuous. Ascribing the diagnosis hasn’t really advanced our understanding.

A diagnostic construction may perhaps have some legitimacy as a categorisation. That – like the idea of an ‘average voter’ – is abstracted away from people’s unique makeups and life circumstances. It picks out certain features of interest and ignores the rest. A categorisation is not though, an explanation. Moreover without any further content to a diagnosis, its application tends to become unfalsifiable. There is no way to confirm or disprove the diagnosis. And most philosophers of science would hold, following Karl Popper, that unfalsifiable claims are not scientific claims.

The assumption remains, although tacitly, that the diagnosis has a one-to-one mapping onto some in principle, identifiable feature of the patient’s biological makeup. Although its specific nature can’t be spelt out, and there is no lab test that could confirm it. It’s taken as read that there must be some common pathology for the diagnosis.

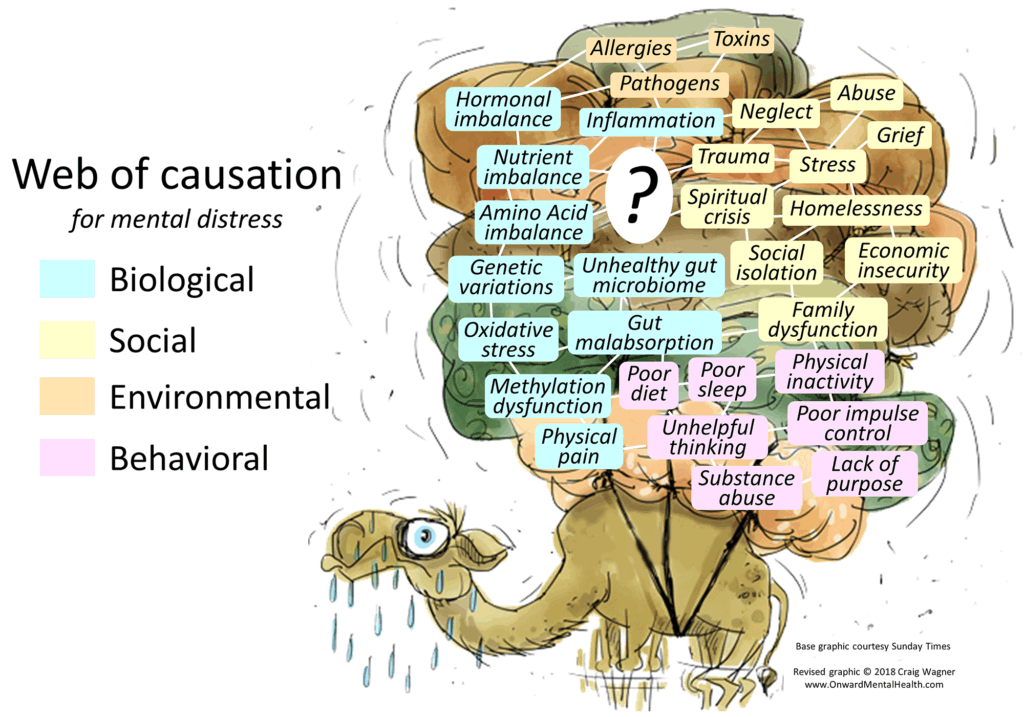

However, the varied epidemiology of ‘schizophrenia’ suggests it is mistaken to assume that there must be a single culprit, or any single cause accounting for its associated signs. A more probalistic, risk-factor stacking approach might be a more plausible working model.

Complex causation & multifactoriality

Complex causation & multifactoriality

It occurred to me that a dam being breached, might be a worthwhile analogy. There is, say, some confluence of factors:

heavy rains over the river basin upstream; after recent deforestation; so more water flowing downstream, faster; the spillway channel around the dam has become blocked-up; the sluice gates haven’t been maintained properly, etc…

Any one factor by itself wouldn’t be sufficient, but many factors coming together is enough for the dam to be breached. This is basically a ‘stress-vulnerability model’. But I hope it illustrates the point that there are often several contributory factors to take into account. And further, that the widest context of environmental, social and psychological influences will play a role in shaping what happens at the, presumedly neurophysiological-level, focal point. One advantage of this dam metaphor is that it fits with schematic talk of upstream causes and downstream effects, sometimes used in neuroscientific models. For instance, Daniel Howes’ Dopamine Hypothesis of Schizophrenia: version III the final common pathway

A model of multiple contributory factors had been put forward by Dale Bredesen for Alzheimer’s Disease. Following his reasoning, many contributory factors mean that treatment interventions should have many targets. He also argues that the ‘amyloid plaques’, targeted in current drug treatments for Alzheimers, should be understood as a defence mechanism of the body. So are more like a symptom rather than the pathology in itself. According to this view, attempting to suppress their growth does little to address their causes.

Some interest groups object to this approach on the grounds that it doesn’t identify and target a ‘common underlying neurophysiological pathology’. But the nub here is whether it’s valid to assume that there has to be such a ‘common underlying pathology’ to target. Even if there is, it may not necessarily be what needs targeting.

Descriptions versus explanations

If, just for the sake of argument, we were to accept that ‘psychosis’ only happens with, say, elevated dopamine synthesis. This would not necessarily mean we have a good explanation for psychosis. To make another analogy. If say, we want to know, why is the water in the kettle boiling? It may help to have a physical description of an ensemble of H20 molecules gaining sufficient kinetic energy to break their inter-molecular bonds, and so on. But a more salient explanation could just be that Mrs Miggins wants a cup of tea!

The micro-level identification may be useful, to an extent, but it is not necessarily capturing the most salient or relevant cause.

We can combine this type of insight, with the neuroscientific analogy of upstream tributaries and a downstream main channel. It follows then, that there may well be more than one way to address any ‘dysfunction’. And moreover, that the drastic option of intervening directly upon the neurophysiological main channel as it were, may be unwarranted.

I think an idea from philosophy of science and mind is also relevant here. The ‘multiple realizability thesis’ proposes that a ‘higher-level’ phenomenon, such as a mental one, could be realized or instantiated by differing sets of ‘lower-level’ physical phenomena. I asked Claude 3 to summarise:

“The core idea behind multiple realizability is that the same mental phenomenon, such as a belief, desire, or sensation, can be instantiated in different ways in the physical brain. In other words, the same mental state could be associated with different neurological or biological configurations across individuals or even within the same individual at different times.”

So, there will plausibly be a many-to-one mapping from neurophysiological states to a mental state, like a psychiatric symptom. It remains then, for a reductionist ‘molecular psychiatry’ to establish grounds for assuming that a specific symptomology could not be realized by different underlying neurological and biological mechanisms.

Dispensing with a disease model

In recent years, there has been increasing recognition that the type of symptoms associated with schizophreniform diagnoses can be quite common. It’s accepted that between 10 and 20% of the population, if not more, experience some level of paranoia. This overlap with the normal range of experience, and the wide heterogeneity in course and outcome found under the diagnosis, suggests that ‘schizophrenia’ might be better understood as an umbrella term, and not a specific disease. Not least, when any specific aetiology for it remains mysterious. Attempts to find genetic markers have failed. Where there may be a link to ‘copy number variants’, this is said to apply only to about 3% of those with the diagnosis.

So, while the type of experiences associated with schizophrenia are seen as quite common, the concept that there really is such a disease has lost credibility.

How could something be commonplace and yet non-existent? Well, Santa Claus appears in many locations each year. And millions of presents appear overnight in children’s bedrooms. But for all that, there is actually no single entity responsible. The role of Santa Claus seems to be multiply realizable. And I’d suggest that explaining millions of individual episodes of psychosis by recourse to a mysterious entity like ‘schizophrenia’ involves similar magical thinking – although far less benignly.

Institutional inertia and diagnostic overshadowing

Although more nuanced approaches to psychosis have been put forward by leading experts, like Robin Murray, it seems this has not translated into broader changes in day-to-day clinical practice. It seems to me that, despite paying lip-service to the many factors that contribute to mental health and ill-health, services, at the end of the day, tend to default to the position that a patient’s issues are basically down to an illness. After all, they have tools ready to use to counter the symptoms, blunt though they are.

This reflexive response can mean that medics stop looking for the causes of a person’s episodes. Assuming that they already know what the issue is, rather than trying to grapple with a more indeterminate reality. Jumping to conclusions, in this way, can mean unnecessary treatment and unnecessary harm.

As appears to have happened in this unfortunate young lady’s case. Having cerebral symptoms due to a rare brain disease, Daisy Simpson’s symptoms were assessed as due to ‘treatment resistant schizophrenia’. She argues, I think fairly, that she didn’t get the right tests and checks, when she should’ve had them, because her issues were so labelled. This resulted in undue delay in her actual brain disease being properly diagnosed.

Overmedicalisation?

In part one, I mentioned an apparent ‘overmedicalisation’ of what are basically people’s problems of living. But a case like Daisy’s appears to be one of ‘undermedicalisation’. I’d argue that it’s the amorphous, almost unfalsifiable, nature of that diagnosis that allows this to occur.

It’s worth exploring what people might mean by saying, “psychiatry is over-medicalised”. I think this is, in some ways, a misapprehension. Historians of psychiatry explain that, in the latter part of the 20th century, the profession tried to disassociate itself from Freudian psychoanalysis. In doing so, it tried to lay claim to a scientific legitimacy it didn’t really possess.

In essence, the logic underlying those claims to legitimacy was derived from the mechanisms of action of certain drugs. Drugs whose efficacy in controlling certain symptoms had been discovered by accident. Joanna Moncrieff has emphasised that we should understand any efficacy of psychiatric drug treatment by reference to the general effects of the drugs (a drug-centered model) rather than a (disease-centred) model that pretends they specifically target a disease’ pathology.

By saying psychiatry is over-medicalised, are we saying?

A medicalised approach is simply not appropriate

or, as psychiatrists like Niall McClaren and Peter Breggin have asserted, that

The biomedical model of psychiatry doesn’t really constitute, or add up to, a medical discipline worthy of the name.

The unreliability of diagnoses and the wide variety in course and outcome suggest psychiatry lacks depth as a medicalised paradigm. Anecdotally, for instance, attempting to find a particular antipsychotic the patient tolerates relatively well is basically just guesswork and trial and error.

Accepting that, for many, mental health troubles originating primarily from adverse psychosocial factors have been overmedicalized. I think it is fair to say there is probably a significant minority whose symptoms stem from causes that are within the legitimate preserve of medical science; for example, the connection with auto-immune encephalitis in some diagnoses of ‘schizophrenia’. And that people falling in this group may receive care that can be said to be ‘undermedicalised’.

A Before and After

Moreover, as discussed before, there is a before and after with psychiatric drug treatment. A complicated prescribing history is likely to mean a greater propensity to kindling and sensitization – where even seemingly minor fluctuations can precipitate crises. If that wasn’t enough, recent survivor research work suggests psychiatric drug treatment can engender auto-immune issues.

As I concluded in part one, these types of effects may be understood as amounting to ‘drug dysregulation syndromes’. These are issues that can be long-lasting and require ongoing efforts from those affected to try to mitigate their impact on daily life.

As I’ve tried to show, the apparent presentation of these lasting effects will tend to overlap with the symptoms associated with certain psychiatric diagnoses. Consequently, these complications have often been mistaken by clinicians as evidence of a worsening psychiatric illness.

There has typically been much resistance in the profession to entertaining this as a possibility.